Existentialism, radical freedom, and anguish

In Existentialism is a Humanism (1946), Sartre formulates his philosophy that “existence precedes essence.” In other words, since human beings have no inherent identity or value, it is through their consciousness that they create their own value and give meaning, or essence, to their existence. This is something individual human beings create for themselves. This goes against more traditional view that essence precedes, or comes before, existence.

Sartre illustrates his argument and asks us to consider a paper-knife. It is made by an artisan who had a conception of it, a formula to which he adheres in order to create a paper-knife that is able to serve a definite purpose. Conceivably, once cannot produce a paper-knife without knowing what it was for. The essence of the paper-knife, that is, the sum of the qualities that make it such, precedes its existence.

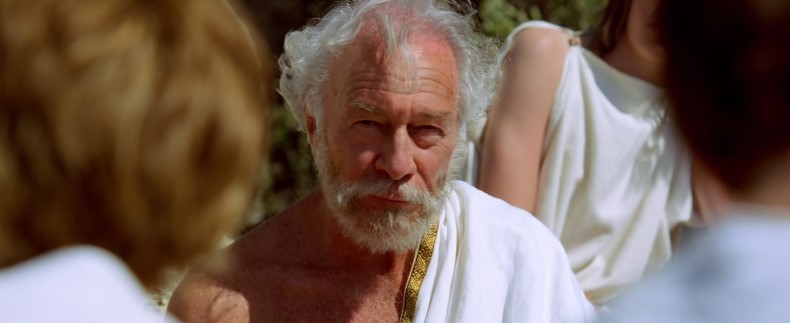

When God makes Man he knows precisely what he is creating: the idea of Man in the mind of God is akin to that of the paper-knife in the mind of the artisan; it follows a definition and a formula. Each individual human being is the realisation of a certain idea that exists in the mind of God. In this sense, in a universe in which God is the creator of everything including human beings, the essence comes before the existence of human beings.

However, in an atheistic universe, one in which God does not exist, there is at least one being which exists before it can be defined by any conception of it. That being is the human being. Man, first of all, comes into being, and defines himself afterwards. There is, therefore, no such thing as human nature, because there is no God to have a conception of it.

Therefore, the first principle of existentialism would be that we have no fixed human nature or morality to determine human action. Unlike a stone, a table, or a paper-knife, after coming into existence, through our individual will we are then free to conceive and make ourselves, create our essence. Before all else, human beings proper themselves towards the future and are aware of doing so.

Radical freedom and the creation of value

Based on this argument, then, Sartre believes that our freedom is radical, or absolute. The first effect of existentialism is that each person possesses him- or herself. We have absolute power to choose how to act in any circumstance we find ourselves in. This places the entire responsibility of our existence squarely upon our own shoulders.

Each of us has a choice, and every act that we choose is freely chosen. We would be lying to ourselves if we were to say that we have “no choice” but to do something. We always have a choice. When we choose not to act, we are still choosing. Therefore, the act of not choosing is still an act of choosing, and with it comes the responsibility of not having chosen.

Furthermore, when we say that the human being is responsible for himself, we do not only mean that we are responsible for our own individuality, but that we are also responsible for everyone else. When the existentialist says that the human being chooses himself, he also means that he chooses for all human beings. Through this choice, by affirming the value of that which is chosen – for we are unable ever to choose the worse – we are also creating an image of what we think is the ideal human being. What we choose is always the better, and nothing can be better for us unless it is better for all. We are creating value.

Thus, our responsibility is much greater than we had supposed, for it concerns mankind as a whole. Our actions are a commitment on behalf of all mankind. In fashioning ourselves, we also fashion mankind.

Anguish

This radical freedom – and radical responsibility – means that we are in a state of what existentialists call anguish. What do they mean by this? When someone commits himself to anything, deciding not only for himself by for all mankind, he cannot escape from the sense of complete and profound responsibility. There is an awareness that dawns on us, that we are ultimately responsible for our actions, and that these actions are examples to everyone else. We are to ask ourselves, what would happen if everyone did so? There is a universal value to our choices and actions. The anguish that comes with that awareness is a pure and simple form of anguish.

When a military leader takes the responsibility for an attack and sends a number of men to their death, he chooses to do it and at bottom he alone chooses. In making the decision, he cannot but feel a certain anguish. That anguish does not prevent their acting. On the contrary, the action presupposes there is a plurality of possibilities. On choosing one of those possibilities, the leader realises that that choice has value only because it is chosen. Anguish, rather than screening us from action, is a condition of action itself.

Abandonment

God’s non-existence has consequences that we need to understand fully. Sartre criticises previous attempts to suppress God at the least possible expense. Sartre explains how previous formulations of secular morality, while denying God’s existence, still claimed that it is essential that certain values – such as to be honest, not to lie, not to beat one’s wife, to bring up children, etc – should be considered to exist a priori all the same. In other words, previous attempts thought that nothing will be changed if God does not exist.

On the contrary, to his horror, the existentialist realises that with the disappearance of God, there also disappears all possibility of finding universal a priori values. There can no longer be any universal, unchanging moral laws that exist independently of us, since there is no infinite and perfect consciousness (i.e., God) to think them. With God’s death, there is now nowhere written that The Good exists, that we must be honest, or that we must not lie, since there now only exist human beings, and those human beings have absolute moral freedom.

Quoting Dostoevsky, Sartre tell us that if God does not exist, then everything would be permitted. As a result, we are forlorn. We killed God and ended up abandoned. We discover that we are without excuse. We have no determinism to blame, no justification or excuse. We are left alone, condemned to be free. Condemned, because we do not choose to exist; and yet, from the moment we start to exist, we are responsible for everything we do.

Despair

Whenever we will anything, there is always an element of probability. Let’s say we’re counting on a visit from a friend coming by bus; we presuppose that the bus will arrive on time. We remain in the realm of possibilities. However, we rely only on possibilities that are strictly concerned in our action. We should not be bothered by possibilities which do not affect our action.

We should, however, be completely concerned with our action, for we are our action! We are nothing else but the sum of our actions. We are not born cowards or heroes; we define ourselves as cowards or heroes through the deeds that we do.