9 logical fallacies you should avoid (with video)

When doing philosophy, the ability to reason properly is a necessary skill. Logical fallacies are mistakes in reasoning. With bad reasoning come bad arguments. Sometimes, these mistakes are genuine and unintentional: merely a lack of awareness on the part of the speaker. At other times, however, these “mistakes” are very much intentional, for example when sophists argue their case.

Part of our training, as students of philosophy, is to learn how to spot fallacies. Why? First, so that when we’re making an argument we avoid such mistakes. Second, so that we are better prepared to sniff out fallacies in other people’s arguments.

Here are nine common types:

- Argument from ignorance

- Appeal to inappropriate authority

- Ad hominem

- Begging the question

- Appeal to emotion

- Appeal to majority

- Appeal to pity

- Appeal to force

- Irrelevant conclusion

1. Argument from ignorance (Ad ignorantiam)

a. “You cannot prove unicorns exist. Therefore, they do not.”

or…

b.”You cannot prove unicorns do not exist. Therefore, they do.”

Ignorance means “lack of evidence to the contrary.”

One form of this fallacy states that something is true because it has not yet been proven false. Another form states that something is false because it has not yet been proven true.

The structure of the fallacy

Let x stand for unicorns exist. Then, we get the following forms:

a. x is false because you cannot prove that x is true.

or…

b. x is true because you cannot prove that x is false.

We can replace the variable x above with any proposition.

More examples

- x = God exists

“God exists” is false because you cannot prove that “God exists” is true.

A more natural way of saying the same thing would be:

God does not exist because you cannot prove that God exists. - x = there is life on Mars

There is life on Mars because you cannot prove that there is no life on Mars. - x = it will be raining in exactly six weeks and two days

You cannot prove that it will be raining in exactly six weeks and two days. Therefore, it will not be raining in exactly six weeks and two days.

2. Appeal to inappropriate authority (Ad verecundiam)

“According to Albert Einstein, who’s a genius, the best way to treat a headache is to drink three doses of cow urine.”

The fallacy

Einstein may be a genius in theoretical physics. This does not mean he’s an equally brilliant physician.

The structure of the fallacy

Let x stand for an expert in field y.

Let z stand for x‘s position on some issue that does not fall under field y.

We then get the following form:

According to x, who’s an authority on y, z. Therefore, z is true.

More examples

We can replace the above variables with other propositions. Here are a few more examples of appeal to inappropriate, or false, authority:

- x = the prime minister

y = social housing

z = Nokia make better phones than Apple

The prime minister is an expert on social housing. He also says Nokia make better phones than Apple. Therefore, Nokia make better phones than Apple. - x = the Archbishop

y = canon law

z = the Nashville Gospel Singers have the most influential guitarist in history

According to the Archbishop, who’s an expert on canon law, the Nashville Gospel Singers have the most talented guitarist in history.

X being an authority on y clearly does not mean s/he is also an authority on z.

3. Against the person (Ad hominem)

“Jake has horrible hygiene and smells exceptionally rancid. His environmental forecast, with regards to global warming, is nonsense.”

“We just caught Mandy stealing an apple from the kitchen. Her argument, that stealing is wrong, is rubbish.”

The fallacy

Also known as argument against the man, this is a type of irrelevant conclusion. Ad hominem seeks to attack someone’s position by attacking the character or personal traits of the opponent, rather than the argument. Such an attack is based on prejudice or feelings that are irrelevant to the argument.

The structure of the fallacy

Person x makes claim y.

The circumstances or character of person x are unsatisfactory, or x does not act according to y.

Therefore, claim y is implausible or unlikely.

More examples

- Ad hominem (abusive)

This attacks the opponent’s character, personality, morality, or competence, which are irrelevant to the argument.

“The Minister for Transport is an arrogant prick. His solutions to solving traffic are deluded.”

Yes, the Minister may be an arrogant prick. And, yes, his solutions may also be deluded. But there is no correlation between the two. We’re basing the conclusion on our dislike of the person. - Ad hominem (circumstantial)

This attacks the motivation of an opponent, claiming it’s a result of personal circumstances, leading to a bias in that person’s judgement.

“The mayor just bought a bicycle and wants to use it. Of course that is his motivation to turn the town centre into a no-traffic area!”

4. Begging the question (Circulus in demonstrando)

“God exists because the Bible says so. The Bible is true because God wrote it.”

The fallacy

Also known as arguing in a circle. Begging the question occurs when an argument assumes the position that is in the question, without proof. In the example above, one must accept the premise to be true for the claim to be true.

The structure of the fallacy

x because y.

y because x.

Examples

- Salvator Mundi by Leonardo is the greatest painting in the world because it’s the most expensive painting ever sold.

While it is true that Salvator Mundi is the most expensive painting ever sold, that does not mean that it is also inherently the best painting. The argument start with an assumption and restates the claim as proof of its truth. - The iPhone is a mobile phone by Apple because Apple makes a mobile phone called the iPhone.

The second half of the sentence is simply a rewording of the first half, in reverse order. - Abortion is evil because murder is evil.

This example of begging the question assumes that abortion is murder, and proceeds to state the claim as proof of its truth.

5. Appeal to emotion (Ad passiones)

“Father Christmas must be a real person. It would be so sad if he wasn’t.”

The fallacy

The fallacy of appeal to emotion is committed when someone tries to manipulate emotions to make their case, rather than building a valid, rational argument.

Appeal to emotion may invoke fear, hatred, happiness, pity, sadness, pride, etc. Many adverts appeal to emotion sway consumers into becoming customers.

Note that, while valid rational arguments may inspire emotions, the fallacy of appeal to emotion happens when emotion is used instead of reasoned argument as a way to convince people.

The structure of the fallacy

x is true because if x were false we would have an emotional reaction.

More examples

- “You should always finish everything on your plate. Think of all the starving children in this world.”

- “The afterlife must be real! The thought of there being nothing is unbearably depressive!”

6. Appeal to majority (Ad populum)

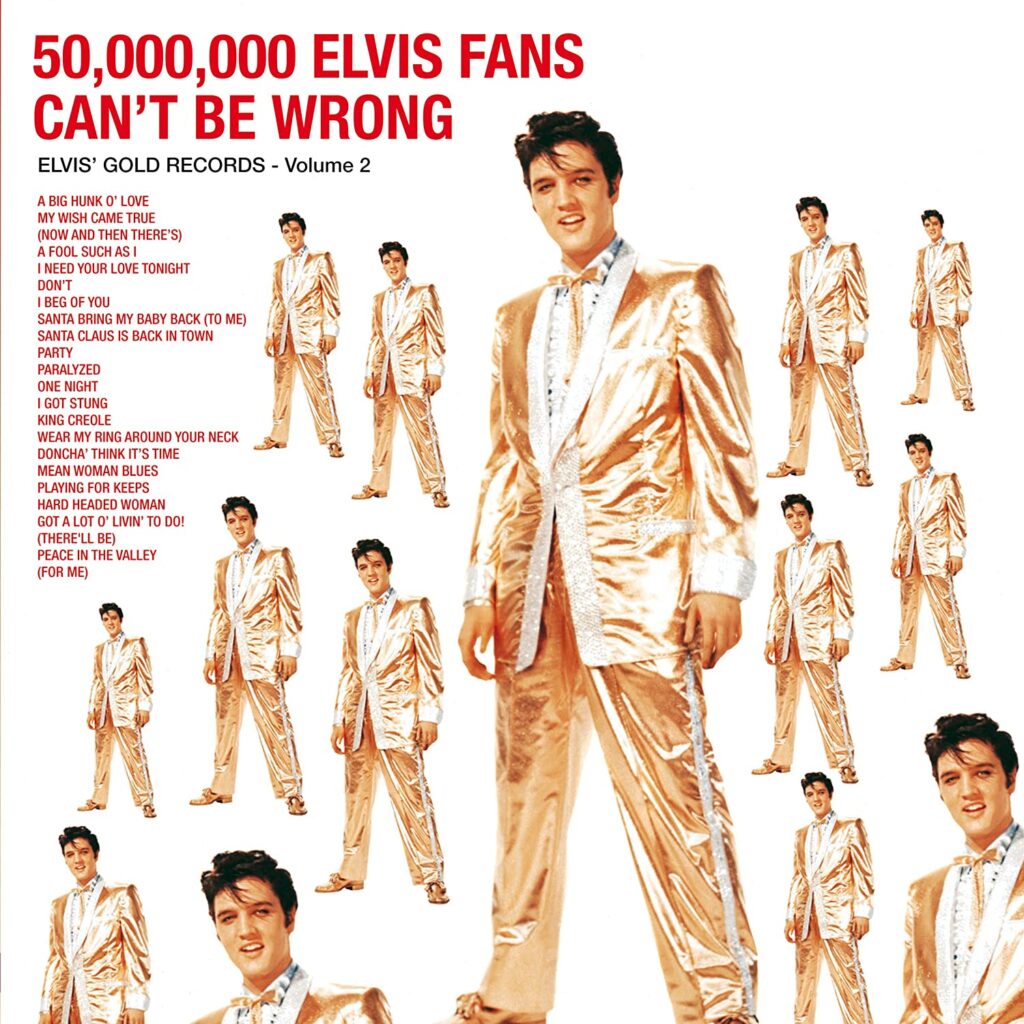

“50,000,000 Elvis fans can’t be wrong.”

The fallacy

Also known as appeal to popularity, argument from majority, argument from consensus, bandwagon fallacy, appeal to common belief, democratic fallacy, mob appeal, and appeal to masses.

The fallacy concludes that a proposition must be true because many or most people believe it. It appeals to the tastes, beliefs, or values of a group of people (Latin: populum)

The structure of the fallacy

Most people believe that x is true.

Therefore, x must be true.

More examples

- The majority chose this government. The majority is always right, therefore, everything this government does is right.

- All of my friends have started a no-fat diet. Therefore, this must be the healthy way to eat.

- Simon’s classmates, who are into sports, make fun of his love of reading. Reading is for nerds, they tell him. Therefore, he gives up reading and signs up for football.

7. Appeal to pity (Ad misericordiam)

“The woman should not be found guilty, since it would break her poor children’s hearts to see their mother taken to prison.”

The fallacy

Also known as the sob story, or the Galileo argument. The fallacy is committed when someone tries to win an argument by exploiting the other person’s feelings of pity or guilt. This is a specific type of appeal to emotion. Often, when deciding a person’s guilt or innocence, the feelings of relatives, or even of victims, are quite irrelevant.

The structure of the fallacy

X is true because not x would be too sad a state of affairs.

More examples

- This election I will vote for Candidate X. She has been trying to run for parliament for the past twenty years and, lately, she has been diagnosed with cancer.

- John should get promoted this year. He has been going through a difficult time at home.

8. Appeal to force (Ad baculum)

“I am right. Agree with me or else I will beat you up.”

The fallacy

Might is right. This is committed when either force or the threat of force is used in an attempt to justify a conclusion.

The structure of the fallacy

X is true. Either you accept it or I will hurt you.

More examples

- “I know it is not part of your duties, but from now on you also need to start cleaning toilets. If you don’t, I will have to start looking for someone to take your place.”

- “You will either spend the day studying or you will be grounded for the next three months.”

9. Irrelevant conclusion (Ignoratio elenchi)

“Polar bears can’t be dangerous because they are extremely cute.”

The fallacy

An irrelevant conclusion happens when the conclusion proved by the author is not the one that author initially tried to prove.

The structure of the fallacy

X therefore y, where x is irrelevant in concluding that y.

More examples

- Mafia members are good with children because they are good with their own children.

- Fibre is healthy for you. Therefore, eating fibrous cardboard is healthy for you.

In conclusion, logical fallacies are pervasive in everyday life, and it’s essential to recognize them to avoid being misled. The good news is that there are several books available that can help you develop your critical thinking skills and avoid these common mistakes.

Here are some excellent books about logical fallacies that I recommend checking out:

“The Art of Reasoning” by David Kelley

This book offers a comprehensive introduction to critical thinking and logical fallacies. It provides readers with the tools they need to recognize fallacies and avoid them.

“The Fallacy Detective: Thirty-Eight Lessons on How to Recognize Bad Reasoning” by Nathaniel Bluedorn, Hans Bluedorn, et al

Here’s a fun and accessible approach to learning about logical fallacies through stories and cartoons. It’s a great choice for those who prefer a more lighthearted and engaging approach to learning.

“How to Think About Weird Things: Critical Thinking for a New Age” by Theodore Schick Jr. and Lewis Vaughn

This book explores how to apply critical thinking skills to a wide range of topics, including pseudoscience, conspiracy theories, and the paranormal, while also discussing common logical fallacies.

“Thinking, Fast and Slow” by Daniel Kahneman

This book provides an in-depth exploration of cognitive biases and errors that can lead to faulty reasoning. It’s not solely about logical fallacies, but it’s an essential read for anyone looking to develop their critical thinking skills.

“The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark” by Carl Sagan

The late Carl Sagan explores the importance of critical thinking and skepticism in a world where pseudoscience and superstition can be alluring. It includes discussions of common logical fallacies and how to avoid them.

If you’re interested in learning more about logical fallacies, I highly recommend checking out one of these books.

Pingback: Philosophy through Don’t Look Up: Inappropriate authority, democracy, and Plato – PhilosophyMT