The Sophists – we are the measure of all things

Today, calling someone a sophist is often meant in an disapproving way. We often use the term for a certain type of individual: a sleazy politician, a shady lawyer, or some other figure good at bending the truth with clever but false arguments. These arguments, while seemingly valid, would be downright superficial and lacking real merit.

The term “sophist” can be traced back to ancient Greece and is related to the word “sophia”, meaning wisdom. Since the poet Homer, sophos referred to someone who was an expert in his profession or craft. Eventually it came to mean someone wise in human affairs such as politics and ethics: the “sages” in early Greek societies.

Who were the Sophists?

Democracy developed in Athens around the 6th Century BC. For it to work, people needed to know how to say things in a convincing manner; we call this “rhetoric”: the art of effective and persuasive communication.

“Sophist” came to refer to a number of lecturers, writers, and teachers of various subjects who lived in Greek cities between the 5th and 4th centuries BCE. They speculated about the nature of language and culture. They also excelled at using and teaching rhetoric. Often, they were employed by wealthy people. Athens, a flourishing city, was the perfect place for them to come together.

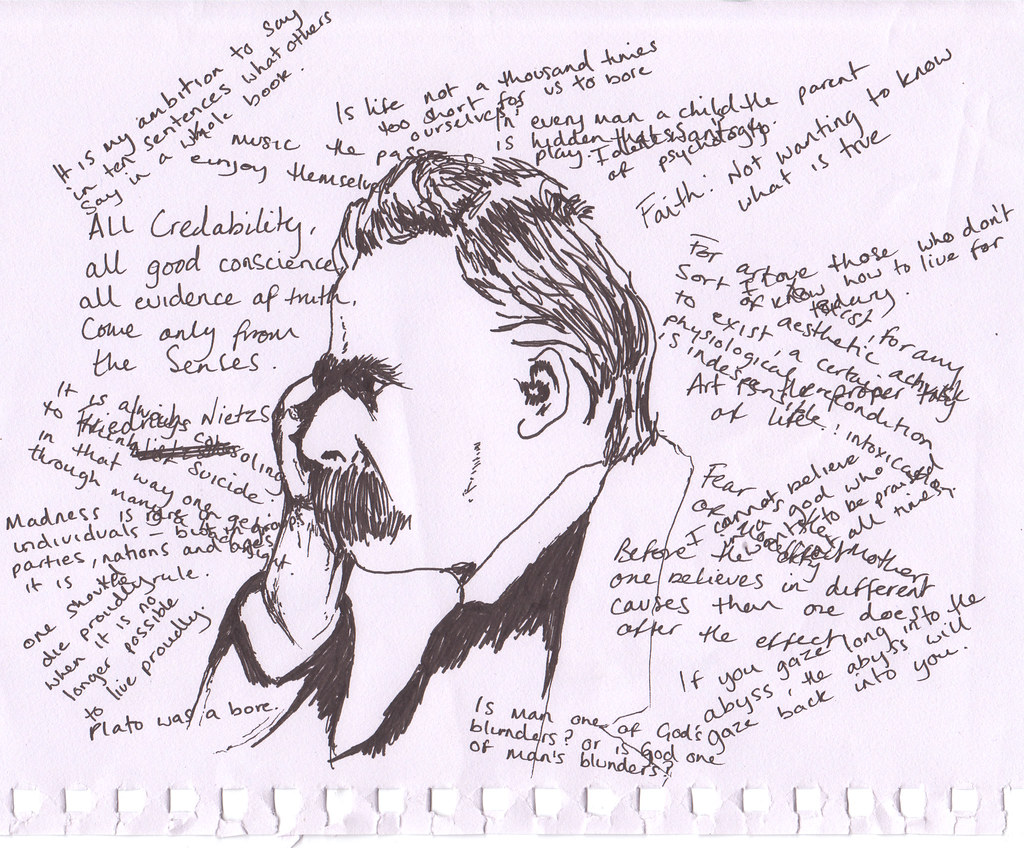

While Socrates embraced and spoke at length about universal and objective truths, the Sophists had their doubts. They spoke of relativism, where truth, knowledge, and morality are not absolute and exist only within a specific cultural, social, and historical context. For the Sophist, knowledge is merely subjective; there is no external or objective truth.

Protagoras: “Man is the measure of all things”

Plato credits Protagoras of Abdera (c 490 – 420 BCE) with inventing the role of the “professional” sophist, one taking payment for his services. He does this in contrast with Socrates, whose only motivation was the truth, not payment.

Protagoras is primarily remembered for claiming the following:

1. “Man is the measure of all things.”

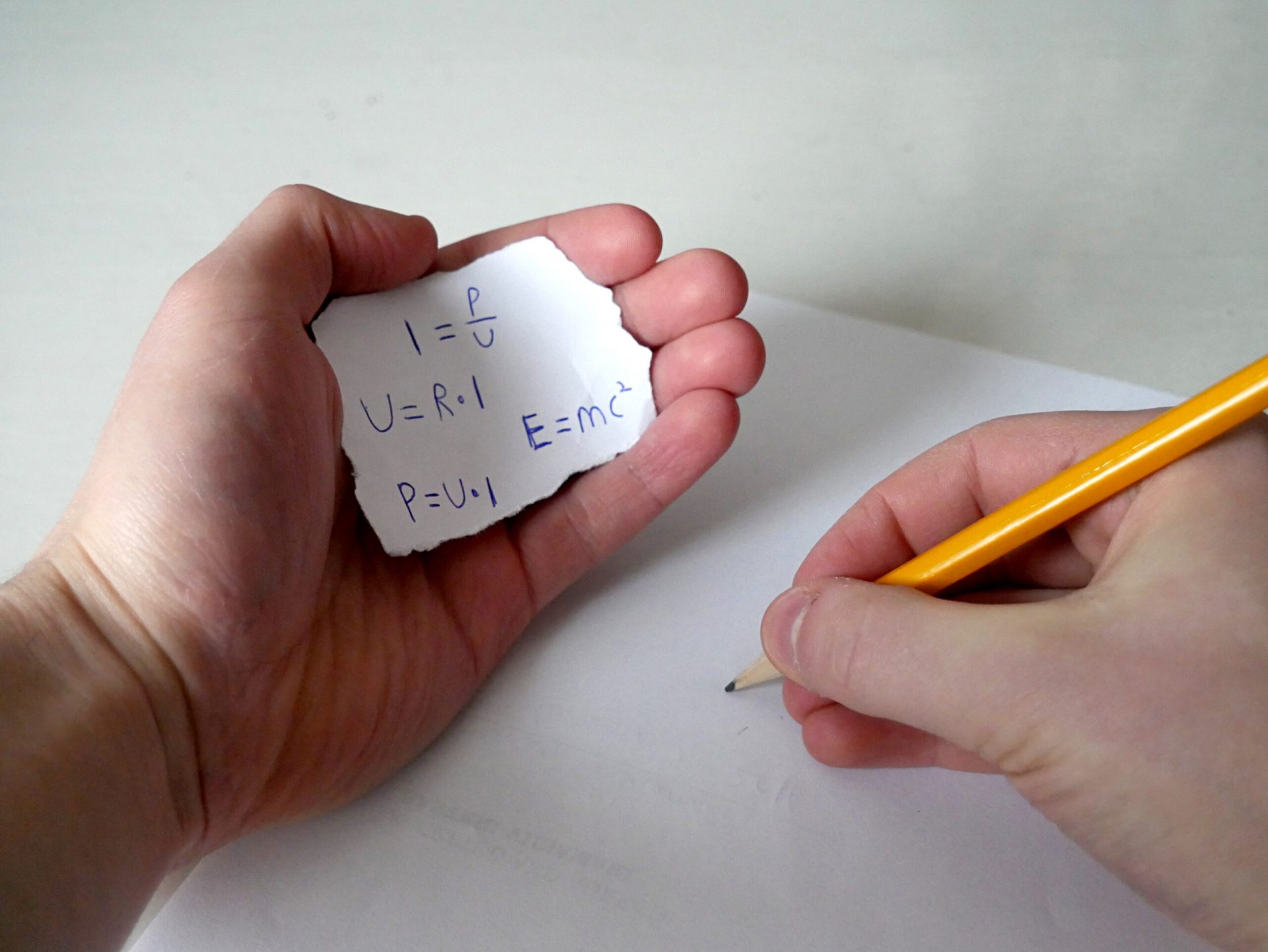

2. He could make the “worse (or weaker) argument appear the better (or stronger).

3. One could not tell if the gods existed or not.

Protagoras would be significantly influential on the development and history of philosophy. His relativism would inspire Plato to search for absolute and objective forms of knowledge that could somehow anchor moral judgment.

Of all things, the measure is man. Of the things that are, that (or how) they are, and of the things that are not, that (or how) they are not.

quoted in Sextus Empiricus’s Adversus Mathematicos VII 60

Gorgias: Moral truth is fiction

Gorgias (483 – 375 BCE) was another sophist figure and rhetorician. Born in Sicily (at the time an ally of Athens), his main occupation was that of teacher of rhetoric. Unfortunately, the vast majority of his writings have been lost to time and considerable alteration by later copyists.

Moral nihilism

He has been called Gorgias the nihilist for his moral nihilism. Nihilism is usually meant as the belief that life is meaningless, and as the rejection of religious and moral principles. Nothing can be really known or communicated.

Gorgias’s arguments could have been found in On Non-Existence, which unfortunately and ironically doesn’t exist any more. What we know of his arguments comes to us through commentary by other writers.

It seems he developed the following arguments:

- Nothing exists. If existence itself existed, it would be either eternal or generated. If it is eternal, it has no beginning and is therefore limitless. If it is without limit, then it is “nowhere”, and therefore it doesn’t exist. If, on the other hand, existence is generated, it has to come from something that exists. However, that something would run itself in the same contradiction just outlined.

- Even if something exists, it is incomprehensible. We can imagine chariots racing in the sea, but that does not make it actual. What happens in the mind is fundamentally distinct from what happens in the actual world.

- Even if we could understand, we certainly cannot convey the content of that understanding to one another. What we reveal to one another is not an external substance, but merely logos – our thoughts about things, which are not the real deal but merely internal, mental representations fundamentally different from the actual world.

As we’ve seen, the Sophists attack notions of objective truth and morality. With Protagoras, truth and morality are relative; it is the individual herself, rather than a god or some unchanging law, that is the ultimate source of value. It’s easy to apply relativism to things that are subject to taste. Let’s take strawberries as an example: if you like strawberries, then you are likely to say that they’re good, whereas if you don’t like strawberries you’re likelier to say that they’re not. In such a case, the terms good and bad are very much joined to the individual. They are qualities that we usually accept as relative to the whoever the subject is. Hence, we refer to taste as subjective. With Gorgias, if we are to consider him a nihilist, even that last bit of moral straw bed is taken from us. Morality becomes a fiction.

When truth loses its universality, things start to get a bit messy even morally speaking. Man not only becomes the measure of taste in strawberries, cars, or songs, but notions such as truth, beauty, justice, and virtue, which Socrates would insist are not subjective but objective and universal, and are subjected to the same relativism.

And here is where relativism starts to face criticism. If what is right and what is wrong is merely what seems to be right and what seems to be wrong to the individual, then how can we make claims such as murder is wrong, or compassion is a good thing? If murder, harm, or rape is not intrinsically right or wrong, then one can construct equally valid arguments for and against; morality itself becomes subjective. We can justify just about anything; all we need is the persuasive skills of an orator. With the right set of figures of speech and appeal to emotions, we can legitimise any act.