Why You Don’t Know What You Want (and How Girard Helps You Figure It Out)

New phone, new watch, new bag, this job, that partner. That weekend trip to Paris in two days.

You finally get what you’ve been craving. Life is gooood! So much going on! Excitingg! you tell your friend in sing-song.

And for a moment it is true; for a moment the new thing lights you up. Yep.

Then, soon enough, predictably, it starts to shine less and less, and you’re left with that hollow feeling that you’re missing something. The next phone? Next watch? A trip to India or Las Vegas, like your friends Simon and Amanda? The cycle repeats.

Why does this happen to us so annoyingly often?

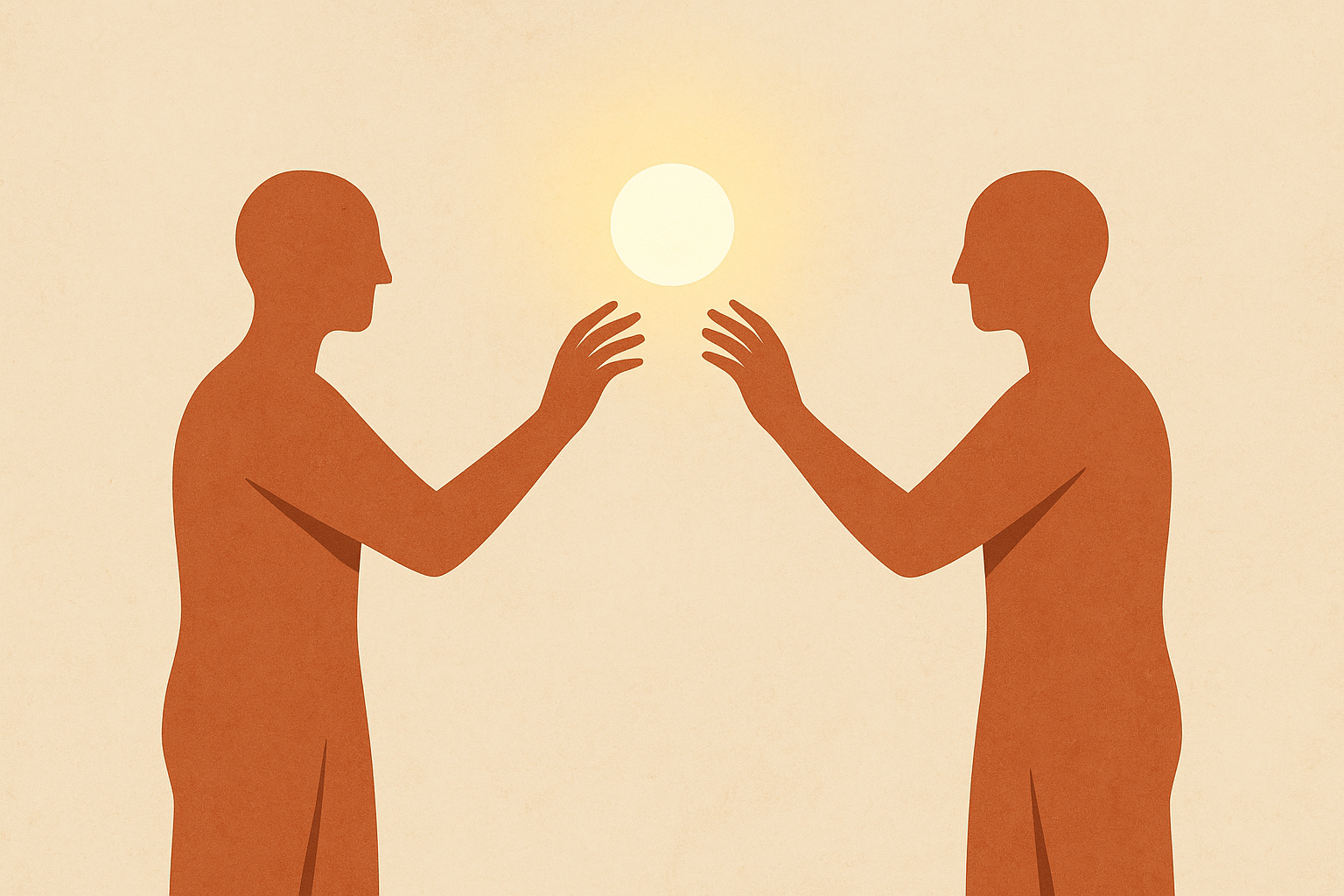

French thinker René Girard (1923 – 2015) had an interesting take: most of our desires are not truly ours. We imagine we want things for their own sake, but in reality we want what others appear to want. Girard called this mimetic desire, from the Greek mimesis, meaning imitation. We copy not just what people do, but what they value. Our models of desire, that is the people for whom we feel some sort of attraction or admiration, teach us what to crave.

Here’s an example of mimetic desire. Picture Lara and Sarah, two children in daycare surrounded by toys. Lara is happily playing with some random toy, until she sees Sarah pick up a different one. Instantly, Sarah’s toy becomes the toy Lara must have. Her desire copies that of someone else. The object itself barely matters. What matters is that someone else values it.

Now scale that up to older, more mature, people. A neighbour’s car, a colleague’s success, a friend’s lifestyle… possibly your own ex – of whom you had gotten bored, please note – on someone else’s arm so now you sulk and desire them again. We take our cues about what is worth having from what seems to attract admiration or envy. Girard observed that this imitation often brings us into conflict. When two people want the same thing because each sees the other wanting it, rivalry begins. The problem is not the object, but the model.

Why it feels personal

We like to think of ourselves as independent minds. The idea that our wants are borrowed can feel insulting. yet it explains much of the anxiety of modern life. Social media, for instance, intensifies the mimetic loop. Every scroll shows what others are chasing. Without noticing, we internalise their desires, making them our own. We then measure our satisfaction by how close we get to their picture of success.

That is why it often feels like we do not know what we really want. Our wants shift with every new model we encounter. The illusion of individuality hides a network of imitation.

Girard did not suggest that we can ever be free from imitation. Desire always has a model. What matters is which model we choose. Some models pull us into rivalry and resentment. Others lift us towards creativity, generosity, or wisdom, echoing what Aristotle said about how to model ourselves after those we consider virtuous people. A model can be toxic or transformative.

A good first step is to name our models by asking ourselves: Whom do I find myself comparing to? Whose approval would secretly please me? Simply recognising the model already loosens its hold. Then, choose better ones. Study people who inspire admiration without competition, those whose fulfilment does not depend on being envied.

Reclaiming desire

To reclaim your desire is not to deny imitation but to direct it. Girard’s insight shows that wanting is a social act. Every choice carries echoes of someone else’s choice. Once you see that, you can decide whose echo you wish to follow.

If you find yourself restless about what to pursue next, pause. Ask not ‘What do I want?’ but ‘Who made me want this?’

The answer is rarely comfortable, but can be liberating.

Want to get your hands dirty? Try this:

- Write down three things you have wanted in the past year.

- For each, note who might have influenced that desire.

- Ask whether the satisfaction matched the expectation.

- Consider what a non-rivalrous model might look like for you – someone whose example encourages peace rather than competition.

Philosophy begins when we question what seems natural. In the case of desire, it starts by admitting that wanting is not always knowing. What feels like our deepest self may, in fact, be an imitation of someone else.