John Locke’s state of nature and the social contract

John Locke (1632 – 1704) is considered to be one of the most influential Enlightenment thinkers. Born in England, he is commonly known as the father of Liberalism and a founder of British empiricism.

What are empiricism and rationalism?

In philosophy, rationalism is the view that sense experience plays little or no part in our gaining knowledge.

Rationalism, exemplified by René Descartes (French), Baruch Spinoza (Dutch), and Gottfried Leibniz (German), contends that there are significant ways in which our concepts and knowledge are gained independently of sense experience. For the rationalists, reason is the source of knowledge. From their view that individuals have innate knowledge or concepts, flowed their belief in intuition. Reason, they concluded, could explain the working of the world without the need to reference sense experience.

It is often contrasted with empiricism, which maintains that knowledge can come only, or at least primarily, from sensory experience.

The principal proponents of empiricism came from the British isles, among them Locke (English), George Berkeley (Irish), and David Hume (Scottish). According to them, individuals are not born with innate knowledge, thus they cannot intuit knowledge. The source of our knowledge are experience and experimentation.

Locke’s empiricism argued that the mind was like a white paper, a blank slate, what he calls a tabula rasa. This would mean that people are born without built-in mental content; they contain neither data, not rules on how to process data. That data and the rules to process is added entirely by one’s sensory experiences. Locke uses this idea to then emphasize that individuals are free to define the content of their character.

Man and the state of nature

The concept of the “state of nature” is a notion in various academic disciplines of what life may be like if there were no societies. It’s a notion found in fields such as moral and political philosophy, religion, social contract theories, and international law.

When trying to understand and define the state of nature, we attempt to answer the following questions:

- What was life like before civil society?

- How did government first emerge from such a starting position?

Locke discusses the state of nature in his second Treatise of Government (1689).

He says how, in their natural state, all people are free “to order their actions, and dispose of their possessions and persons, as they think fit, within the bounds of the law of nature.”

Locke’s state of nature is a state of perfect and complete liberty. In it, we are free from the interference of other people. In Locke’s state of nature, there are no politics to contend with; it is, therefore, a pre-political, pre-governmental state.

However, despite it being a state with no politics or government, it still is a state prescribed by moral laws.

Locke continues that “the state of Nature has a law of Nature to govern it.” That law of nature is a moral code handed to Man by God and prohibiting us from harming one another.

Since, according to Locke, we are al equal, we are all equally capable of discovering and being restrained by natural law. We can know and follow that natural law through reason. Reason teaches us that “no one ought to harm another in his life, liberty, or property.”

By reason we can be brought to realise that everybody will be better off and will have better opportunities, if they enter a social contract. We will pick up the idea of a social contract again further down.

The three natural rights

The law of nature, or theory of natural law, is a theory that says that people have inherent ethical values that govern how they reason and their behaviour. These rules, being part of nature, are not created by society but are as transcendent and as universal as, say, the laws of science. Being universal means that they apply to everyone, everywhere, in the same way.

According to Locke, the law of nature obliged all human beings not to harm “the life, liberty, health, limb, or goods of another.”

Since natural law is universal, and we are all equally God’s children (and we cannot take away that which is His), then it would follow that all individuals are equal in that they are born with certain inalienable natural rights that are fundamental; they can never be taken or even given away.

These fundamental rights can be summed up as:

- life,

- liberty, and

- property/possessions.

Fundamental to this view is the corresponding duty of the individual to respect those same, equal rights of others and, therefore, to refrain from impairing or harming those rights.

The social contract

In a state of nature, people protect these natural, fundamental rights, that is life, liberty, and property, by using their own strength and skill.

The theory of the social contract postulates that our moral, social, and political rights and obligations arise out of a tacit, or implied, agreement. It is an agreement between the members of society to uphold certain rights and responsibilities, with the intent of protecting those members of society.

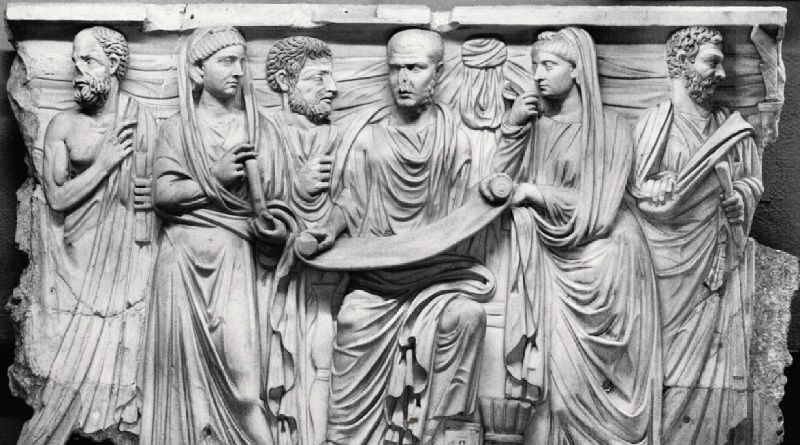

The theory has a long history that can be traced back to Socrates’ explanation to Crito why he has to accept the death penalty. However, it is nowadays associated with modern philosophy, ethics, and political theory thanks to the works of Thomas Hobbes, Locke, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

For Hobbes, the state of nature is a state of war. While rejecting the notion that monarchs have their authority invested in them by God, Hobbes also rejects the idea that power should be shared between the monarch and Parliament. The monarch must have absolute authority to keep society from falling back into, what he considered, an utterly brutal and intolerable state of nature.

However, Locke’s state of nature is very different from Hobbes’.

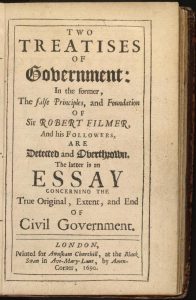

His arguments are mainly found in his Two Treatises on Government.

In the first Treatise he focuses on refuting the idea that political authority was derived from God, sometimes called the Divine Right of Kings. There had developed a tradition in medieval Europe that kings (and queens) were chosen by, and derived their power and authority directly from, God. This implied that their power on Earth was absolute and could not be judged or held accountable by any earthly authority, such as a court of law or parliament.

Locke replies that the establishment of governments (including kings) is only justified on the basis of that government providing protection of the people’s property and well-being. When governments devolve into tyranny, such as when they deny people the right for self-preservation, then the tyrant puts himself in a state of nature, and specifically into a state of war with the people. This means that the people now have the same right for self-defence as they had before establishing the social contract.

Since for Locke the state of nature is not as bleak as that of Hobbes, there are certain conditions under which it would be preferable than having tyrannical governments. In that case, the people would be better off revolting, to establish a better government. The risk of falling back into a state of nature, while laying the foundations of a better government, then becomes worthwhile.