Aristotle’s metaphysics

First of all, what is metaphysics?

Metaphysics is one of the main branches of philosophy, along with ethics, aesthetics, logic, epistemology, and others. Aristotle calls metaphysics “first philosophy”, and says that it deals with “first causes” and the “principles of things,”

Metaphysics is concerned with questions about the fundamental nature of existence, being, and the world. It tries to answer questions about how things are and about how things change to become something else. It examines the relationship between mind and matter, between substances, or the individual “things” in the world, and their attributes, or characteristics.

Why is it called metaphysics?

The word derives from Aristotle’s own works in Greek, with meta meaning “after” and physika meaning “physics.” The term is thought to be the result of an editorial decision by Aristotle’s editor, Andronicus of Rhodes, who placed the books on first philosophy right after the works on physics, and called them, quite literally, “the books that come after the books on physics.”

However, in more recent times (such as the middle ages), it also took on a new meaning, referring to the study of that which is beyond the physical.

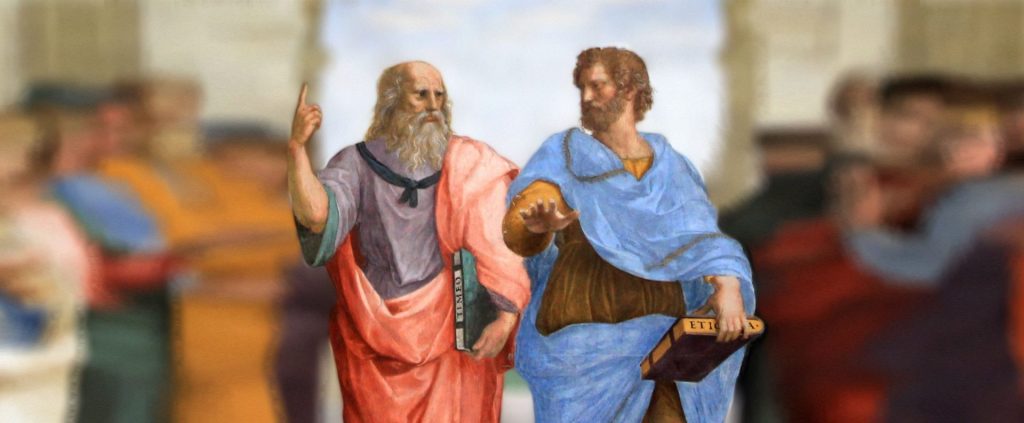

In Metaphysics, Aristotle criticizes Plato’s theory of Forms. For Plato, the Forms are the perfect, ideal, eternal things to which correspond those perishable things and properties that we find in the world. For Plato, the Forms are abstract things, existing completely outside space and time.

For Aristotle, Forms do not exist independently of things. They are intrinsically linked to objects. For things to exist, they have to have both substance and form.

Plato, on the left, points upwards, towards an otherworldly realm of unchanging perfection, while Aristotle’s right hand seems to be grounded on an earth we know and experience through our senses.

Aristotle felt that Plato’s theory of Forms does not address change.

Being and becoming

The issue of change went back decades and centuries from the time of Aristotle. Most notably, the pre-Socratic philosopher tried to make sense of a changing world, seeing it go from season to season. They saw how living things grew up, matured, then broke down and died. When things died, they decomposed.

The two major pre-Socratic philosophers traditionally associated with the issue of change are Parmenides and Heraclitus. Parmenides is known for his view that change is but an illusion: nothing changes. There is a pure, perfect, and eternal being behind nature, and this is the ultimate truth of being. Heraclitus, on the other hand, believed that everything changes, everything flows (panta rhei); one cannot step in the same river twice.

It is difficult to tell what Heraclitus’s river is because it is constantly becoming something else; the present moment is ineffable, ungraspable, constantly shifting and fluctuating. In contrast, Parmenides’s being, or reality, is still pretty much ineffable, although what makes it beyond description is that it lies beyond experience.

Things that are have being. When things exist, they have being. To say that a table is, is to say something about being. Moreover, to say that a table is, say, blue, also says something about being. Becoming also says something about being: it says something about the possibility of change in a thing that has being.

Potentiality and actuality

Things that have being have actuality. They actually exist in reality, for a fact. Actual things are things that have form.

However, actual things also have potentiality. They have the possibility to have forms other than their current one, if they currently actually have one, These new forms are not yet actual, they do not yet exist; they have the potential to exist.

Taking an acorn as an example, given the right conditions it will eventually develop into an oak tree. The acorn has actual existence; it really exists in the world and I can hold it in my hand. It has weight, colour, texture, smell, and taste. I know it when I see it, and I also know that given the right amount of light, water, and soil, it will germinate into a beautiful oak tree. When I’m done smelling it, I can put it in my pocket and carry it with me all day, and perhaps forget it’s there.

However, I can’t say that I am holding an actual oak tree. What I am holding is a potential oak tree. Why? Because the acorn has the potential to become a tree.

Things that have the potential to develop into something are said to have an end, purpose, or aim. Aristotle called this telos, or final cause.

Aristotle’s four causes, or four explanations

Aristotle’s metaphysics often revolved around his idea of the four causes, the four types of answers to the question, “why?”. The specific Greek technical term used by Aristotle is αἰτία, traditionally translated as cause, but to which the closest current everyday translation would be explanation.

In Physics and Metaphysics, Aristotle lists four types of explanations to answer “why” questions:

- Matter, or hū́lē

The stuff or material out of which something is made. In the case of a table, this might be wood; in the case of a book, paper. - Form, or eîdos

The shape or appearance of something. In the case of an orange, this would be close to a sphere. - Agent, kinoûn, moving cause, or efficient cause

Anything, other than the thing itself, that causes the thing to change or move. A table’s agent, mover, or efficient cause would be the carpenter. A child’s efficient cause would be the parent. - End, telos, final cause, or purpose

The sake of which a thing is what it is. The telos of something would be its potential to take on an end form. A caterpillar should, finally, become a butterfly; its nature will cause it to reach that final stage.

In the next article we will be looking at how Aristotle explains man’s place in nature and our function.