Hammering Art to Save Earth: Just Stop Oil’s Gallery Protests

This article first appeared in Philosophy Share issue 20, December 2023.

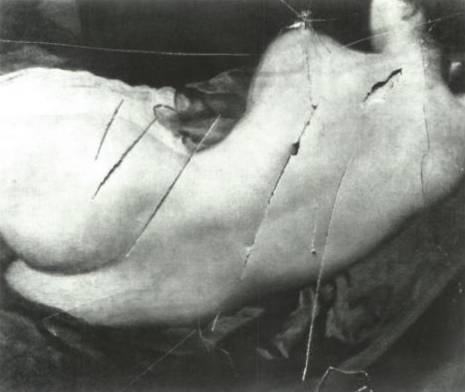

On October 6th, 2023, in London’s National Gallery, members of Just Stop Oil, a climate activism group, raised their hammers not against the anvil of environmental policy, but upon the glass safeguarding Diego Velázquez’s The Rokeby Venus. The protest is as visually striking as it is controversial. While the glass shattered, the painting itself was lucky enough to escape damage.

This is not the first time Just Stop Oil have used artistic treasures to protest. They’ve glued, splattered, and now, hammered their message home, insisting that the UK government cease all new fossil fuel projects. The group’s methods are undeniably provocative, the Velázquez chosen with a historical resonance. In 1914, Mary Raleigh Richardson, a suffragette arrested nine times for her activism, slashed and gashed this same painting with a meat cleaver.

In 2023, the activists’ narrative is clear: urgent times call for urgent measures. But as they tread the tightrope between activism and art, between rebellion and reverence, the question looms: does this fusion of protest and performance herald change, or merely spectacle?

The list of Just Stop Oil targets also includes a Van Gogh, a Vermeer, and a Constable — a pantheon of artistic deities whose works have been made unwitting conscripts in a war against fossil fuels.

In 2022, on June 30th, two supporters glued themselves to the frame of Van Gogh’s Peach Trees in Blossom at the Courtauld Gallery in London. A few days later, on July 4th, another two glued themselves to John Constable’s The Haywain at the National Gallery, covering the painting with a printed illustration that reimagined The Hay Wain as an “apocalyptic vision of the future” that depicted “the climate collapse and what it will do to this landscape”. A day later, more supporters glued themselves to a full-size copy of Leonardo Da Vinci’s The Last Supper at the Royal Academy of Arts, spray-painting “No New Oil” on the wall just under it.

More protests followed, including throwing tomato soup on the fourth version of Van Gogh’s iconic Sunflowers, on October 14th at the National Gallery, and more glued protesters, this time and for the first time outside the UK, to Vermeer’s equally iconic Girl with a Pearl Earring at the Mauritshuis in The Hague, on October 27th.

More such protests followed, including throwing tomato soup on the fourth version of Van Gogh’s Sunflowers (on October 14th), housed at the National Gallery, and more glued protesters, this time, and for the first time outside the UK, to Vermeer’s equally iconic Girl with a Pearl Earring at the Mauritshuis in The Hague (on October 27th).

This crusade, punctuated by glue and soup rather than chisels and explosives, seems to straddle a fine line between homage and sacrilege.

Each act of protest by Just Stop Oil bears a watermark of the past. They seek to wield the historical heft of these artworks, yet their methods are marked by a certain hesitance. Is it respect for the art, a recognition of its sanctity, or simply a recognition of legal and societal boundaries that stay their hand from crossing the Rubicon of actual destruction?

This reticence, however, does not diminish the disquiet that such acts engender. The idea of art under attack — whether by the application of soup or the sharp tap of a hammer — strikes a discordant note. It is as if Just Stop Oil, in its quest to awaken us to one existential threat, inadvertently reminds us of another: the fragility of our cultural touchstones, which, once lost, are irrevocable in their absence.

Vandalism as Rebellion

These acts seem to carry something of the scourging – if rebellious and defiant – spirit behind vandalous graffiti and spray-paint tagging on public walls and historical monuments in cities like Athens, Rome, or Paris.

Granted, tagging gives vibes of apathy, ruinous youth, and a lack of appreciation for patrimony. It results in an urban decay far removed from the sanitised aesthetics of touristy postcards. Arguably, it makes places feel less safe, less pretty.

But at the same time, it blows the lid off the less desirable aspects of real life: social isolation and fragmentation, marginalisation, abandonment, dissatisfaction, and disillusionment.

Tagging is, quite literally, superficial and – at the cost of sounding simplistic – reversible: nothing a good cleaning can’t fix. It defaces but doesn’t quite annihilate its targets. Of course, cleaning and restoration are costly and annoying – especially if the tags keep coming back with a vengeance by the next day – but relatively easily accomplished.

But condemning acts of vandalism and sending in the power washers, while commendable, should be but the first step of a cathartic, more permanent process. We must see them as a symptom, rather than the illness itself. We must pursue a deeper understanding of their sources and a truthful, society-wide commitment to fix those same sources.

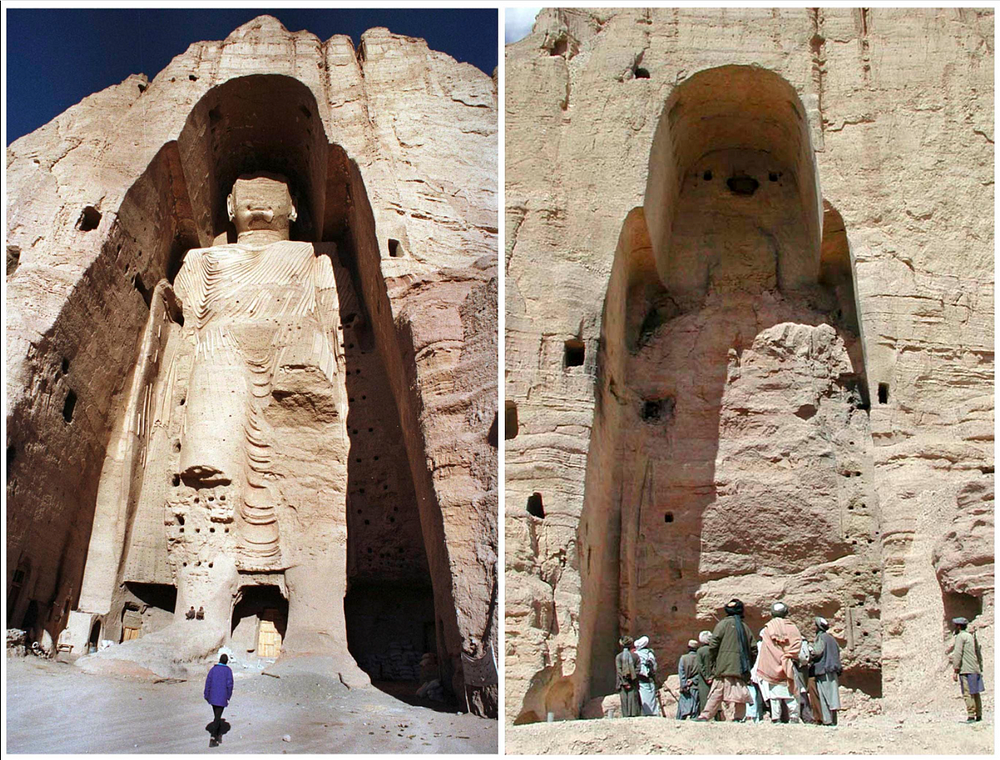

Compared to tagging, the damages caused by the Just Stop Oil protests are equally superficial and equally, if not more easily, reversible. At their worst, these acts have gone glass-deep in their destruction. Their artistic targets, while highly recognisable, have escaped largely unscathed, at least this far. Therefore, Just Stop Oil are not quite the villains of cultural heritage, unlike the dreadful acts of the Taliban destroying the Bamiyan Buddhas in 2001, to name one distressing example. Even locally, over the years, we’ve seen sustained, permanent acts committed on Maltese natural and cultural heritage by the very institutions meant to protect it, far worse than glued hands and splashed tomato soup on protective glass.

Earth versus Art: Destroying to Create

Given the damage from these protest acts is negligible, then why do we get so worked up about them?

Just Stop Oil flirt with a paradox. To get their message across, they encroach upon and risk the sanctity of world-class artistic heritage, the same sanctity they champion for our natural environment.

The targets are canonical masterpieces. They are unique, individual works with their place not just in the history of art, but in the long story of human ingenuity and creation. This uniqueness about them is reminiscent of the uniqueness of the Earth itself. Both these works and the Earth possess an irreplaceable quality, a thread of continuity that, once severed, cannot be reknit in the same way.

Why do many spring up at these protests but are unperturbed by global warming, or the Great Pacific Garbage Patch? What do we value more? Singular examples of past human artistic achievement, or the future of our planet, with its incredible biodiversity, dazzling landscapes and ecologies, and the promise of more singular human accomplishment, terrible, beautiful, and sublime? It’s a false dichotomy, but one that serves its function of making us think.

Perhaps the artworks feel more tangible. They are present and we experience them in their immediacy. They are perceivably finite. Their degradation and loss would be concretely immediate, and therefore more acutely felt and more visceral. On the other hand, the issues surrounding the ecological future of the Earth seem more abstract, more difficult to grasp. They come loaded with misinformation, scientific illiteracy, and appeals to inappropriate authorities. They are sliced between accusations of delusional scaremongering on one hand, and bribery and corrupt dealings such as the Panalpina case on the other.

Smashing the Past to Birth a Future, Almost

Just Stop Oil may have inadvertently stumbled upon a new kind of performance art. It’s one where the crescendo stops shy of the climax, where the hammer is stayed by the glass — an alarming spectacle of, let’s call it, almost-violence. There is not the visceral finality of Ai Wei Wei’s calculated shatter of a 2,000-year-old Han Dynasty urn, an act he transformed into a searing critique of cultural amnesia. His 1995 performance, aptly titled “Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn,” was a deliberate, irreparable act of destruction. Reacting to accusations of desecration, Wei Wei retorted sardonically, “Chairman Mao used to tell us that we can only build a new world if we destroy the old one.” Despite the powerful message, one can’t help but feel gutted at the loss. Art doesn’t always have — isn’t always meant — to be beautiful. It can be horrifying and, through that, provoke change.

In contrast, Just Stop Oil’s gallery protests, while resonant with the same theatricality, lack the final destructive act of Wei Wei. They are a prelude without a conclusion. They leave us in a state of suspended – if dreaded – anticipation. Their performances, staged with the dramatic flair of a heist movie, seem to end just as the plot thickens. Therefore, given that there is no irreversible damage, can we grant these protests the same gravitas as Wei Wei’s urn?

Driving the Hammer Home

Here’s one way to judge the effectiveness of these protests: it resides not in the act of destruction but in the public’s visceral response to the mere threat of it. From the news coverage, the activists seem to have not marred a single brushstroke of the works they have targeted. Yet, the anxiety stirred is palpable. We’re watching a trapeze artist teeter without a net — all it takes is a momentarily unsteady hand, a blow landed too far.

Therefore, the answer may lie not in what is broken, but in what such acts break open in the collective consciousness. Just as Wei Wei’s urn sparked dialogue on the value of social and cultural structures, that of Just Stop Oil is an art of the unfulfilled threat, focusing on one of society’s paradoxes — venerating the relics of the past while jeopardizing the heritage of the future.

It’s a performance that, while lacking the finality of Ai Wei Wei’s shattered urn, leaves its audience in a similar state of reflective disquiet, pondering the fragility of both our planet and the human expression it has allowed to flourish. Unlike Wei Wei’s act, these protests allow us a small flood of relief that the artefact is still there. Their act sparks a counter-factual exercise to reflect on what could have been but, luckily, isn’t.

Just Stop Oil, to make us aware of one existential threat, remind us of another: that heritage, be it cultural or natural inheritance, once destroyed, is irrevocably gone. We moral, rational agents, wielding the power of stewards, are the ones who must be roused to the perils of environmental apathy.

What are we willing to hammer in the name of progress?

— — —

Sources

Climate protesters glue themselves to Constable masterpiece. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-london-62038615. Accessed 7 Nov 2023.

Ai Wei Wei Dropping Han Dynasty Urn, 1995. Guggenheim Bilbao. https://www.guggenheim-bilbao.eus/en/learn/schools/teachers-guides/ai-weiwei-dropping-han-dynasty-urn-1995. Accessed 7 Nov 2023.

Bribery in the Oil and Gas Industry: The Panalpina Bribery Scandal. National Whistleblower Center. https://www.whistleblowers.org/bribery-in-the-oil-and-gas-industry/. Accessed 8 Nov 2023.

Just Stop Oil. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Just_Stop_Oil. Accessed 7 Nov 2023.