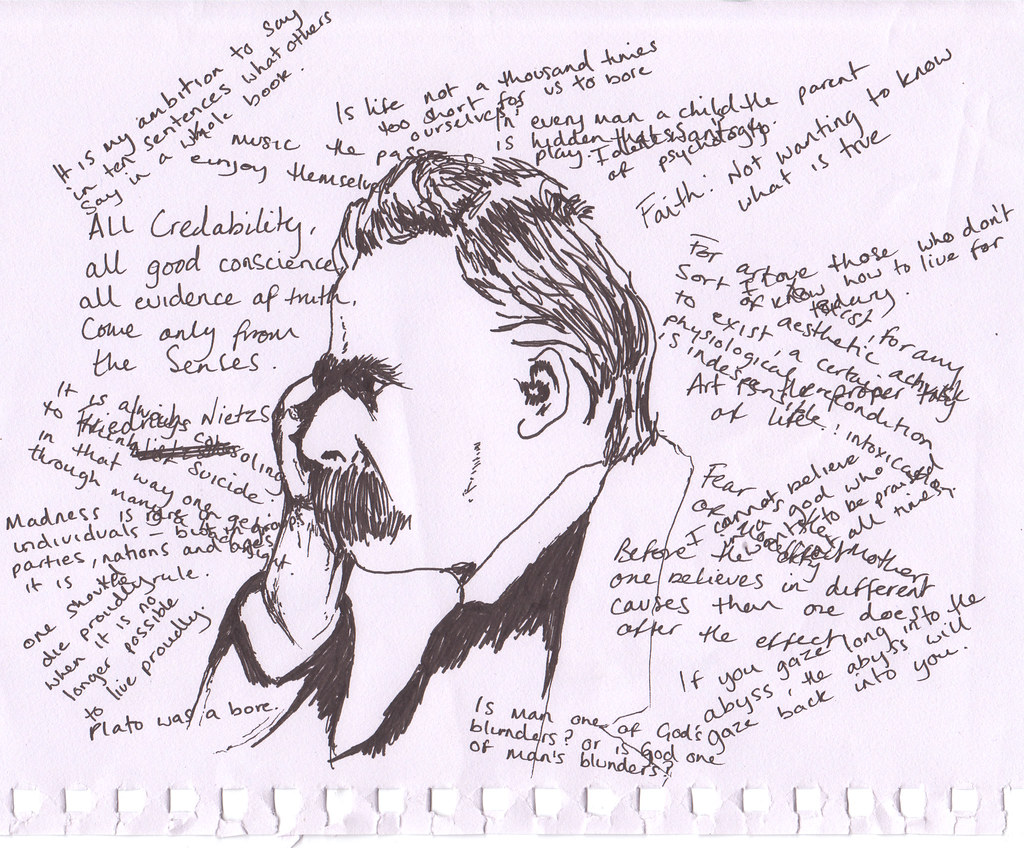

Nietzsche and the crisis of morality

Modernity started in the sixteenth century and reached its peak around and in the decades after the time Nietzsche was active. With it came a shift in the way the West saw humanity’s place in the world and the universe.

Starting with Polish astronomer Copernicus, Earth no longer stood at the centre of creation. Science relegated it to a more humble place in a solar system centred around a star, the sun.

The Catholic Church fiercely rejected this idea. Why? Because:

- it demoted human beings, hitherto created in the image of the almighty God, to the periphery; and

- it went against Aristotle’s scientific theories, which the Church had been endorsing for centuries.

If it started to accept this new universe, then it would be contradicting its own claim to infallibility.

Almost a hundred years after Copernicus, the Church would keep Italian scientist Galileo under house arrest for the rest of his life; he dared to say what Copernicus had said before him.

The simultaneous fall and rise of humanity

However, holding back the floodgates proved to be incredibly difficult. The advancement of science, coupled with increasing doubt about the divine order of things and society (think the French revolution), and a movement towards secularisation slowly but surely eroded the bedrock of religion.

With discoveries in electrical energy, lightning could be explained in terms of natural electrical force rather than a weapon of the God of Thunder. Rain and floods became natural phenomena based on atmospheric conditions rather than expressions of love or anger by some wet blanket of a god.

Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection, initially laughed at, neatly explained how different species come to exist, including human beings, without the need of God’s input, part of a web of causes that comprises the whole universe. It put us closer to apes than angels. We occupy no privileged place over other animals.

Man lost stature in the grand scheme of things. However, that loss found itself offset by growth of a different kind. Although God may not have made us in His own image, we can now understand how the universe works. We just have to put our minds to it.

Ironically and interestingly, man’s diminishing place in the grand scheme of things matched itself in our trust in our abilities to understand that same grand scheme of things: the universe and the natural laws that govern it. For a while, philosophers like Kant thought that we can use reason for moral guidance. Nietzsche disagrees. According to him, we act just like other animals, primarily governed by our instincts rather than reason.

God, exit stage left

Slowly, but surely, God’s place in the universe shrank.

“God is dead”, Zarathustra said in Nietzsche’s Thus Spake Zarathustra, “and we have killed him.”

Morality had been the domain of religion for centuries and millennia. The gods had been handing us the laws of good and evil, through prophets, priests, oracles, and holy men.

Now, if God is dead, then so die any divine moral rules attributed to him.

Bereft of these rules, we are then left to fend for ourselves, left to figure out our own rules. Moral values stop being “real”; they stop being facts in nature that stand in and of themselves. Much like the sophists, Nietzsche concludes that values are something we fabricate: a fiction.

Where do we go from here? Read more in the next essay.